If you read my last post, you know I was recently rocked a bit by a breast cancer diagnosis the week after I got back from the IASP World Congress on Pain. I‘ve been navigating healthcare appointments and treatment in the weeks and months since and still haven’t really processed all of this yet. I’m still going through it, and haven’t yet been able to reflect on much of anything.

So I fell behind on writing here, but am keen to get this post out on vigilance and pain, which I started (and damn near completed) before the cancer diagnosis. I actually had it scheduled to go out on November 6th, then was further rocked by the election results. I am not okay. Cancer treatment plus an election that is going to do so much harm to so many is a lot. I have to be even more vigilant these days, as are so many others. Which is why I’m going to publish this, even if I can’t quite gather my thoughts the way I’d like to.

To start, let’s head back to my pre-diagnosis summer, when I was preparing to present on patient and public involvement in pain research, as part of the ENTRUST-PE Network, and to chair the Pain and Trauma Special Interest Group symposium. I was asked to chair the trauma and pain symposium to ground the session’s talks in lived experience, contextualizing the research on trauma and pain and the implementation of trauma-informed practice through the lens of a person who has experienced both. I was grateful to be asked, because trauma and pain are not abstract concepts or academic puzzles to solve. Trauma and pain happen to real people. Like me. Like you. Like someone you love or work with or care for or know.

The session went really well, surprising some of the academics in the room who aren’t used to lived experience being interwoven throughout a session on pain research and practice. (As you probably know, my personal bias is that all sessions should include a lived experience perspective, how better to make research and practice recommendations more relevant and actionable?) This session built on the one I moderated on trauma and pain at the Canadian Pain Society meeting last year, with Mel Noel and Richelle Mychasiuk. Mel and Richelle presented with Gary MacFarlane at the World Congress and, let me tell ya, it was a masterclass in weaving together clinical practice, basic science, and epidemiology, all grounded in the lived experiences of real people.

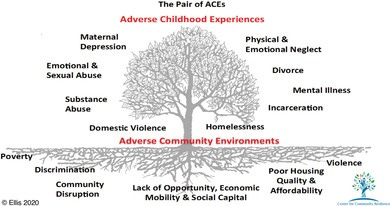

In that talk, Mel and Gary introduced me to the concept of Adverse Community Environments, in addition to Adverse Childhood Experiences, to better account for things like poverty, violence, lack of opportunity, racism, discrimination, sexism - all the isms (the social in biopsychosocial that has been neglected in most pain research and care), and it really got me thinking about vigilance and pain, and how it related to what I what I said during the symposium on trauma and pain a few days earlier.

I’m going to try and capture all of that in this post, and I’m really curious what you all think. Below comes from the notes I shared with the Trauma and Pain SIG folks ahead of our symposium, with some added thoughts as I try to bring this all together through my breast-cancer diagnosis and treatment befuddled brain.

I'm not going to share my trauma, but I will share how it's shaped me and what I've learned from reflecting on my trauma and pain over the years. When I first learned about the links between trauma and chronic pain I was angry. Furious. Enraged. I had a visceral response. I was shaking with…with what? Why was I so mad about hearing these connections between trauma and pain?

Thankfully, I was in a good place at the time and I got curious about that response. I was able to reflect on my experiences, dig around, explore where this rage might be bubbling up from. Here’s where I’ve landed thus far.

There I was, in my early 30s, experiencing chronic pain. During the dark years of my pain, when the pain wasn’t getting better like it should have, I wasn’t always believed, or taken seriously. I felt blamed for my pain, that I was the reason I wasn’t getting better. There wasn’t something wrong with my hip, there was something fundamentally wrong with me. I felt immense shame. Shame that I somehow wasn’t doing this pain thing right. Shame that I had let my fellow firefighters down, especially the women who worked so damn hard to prove that we belonged there. Shame that I wasn’t the same wife, daughter, friend.

Sounds familiar…

And damn, wasn’t that similar to experiencing trauma as a tween-and teenage girl? When I didn't tell anyone what happened to me because I was ashamed? Worried about being blamed? Worried I wouldn't be believed or taken seriously? Worried I’d let other people down, especially the women in my life? I’d let it happen to me.

The parallels are striking, and made me realize why I was so angry and resistant when I first learned of the links between trauma and pain. As a woman who had experienced trauma and now had chronic pain it was like a triple whammy of stigma and shame. And I didn't want to be stigmatized again. I didn't want to be victimized again. I didn’t want to be blamed. I just wanted to be normal. Not other, abnormal, dysfunctional, just wrong somehow.

Like all outsiders, [our] powers of observation derive from alienation and its tenant twin, vigilance.

Steve Almond, Truth is the Arrow, Mercy is the Bow

Oof that quote really hit home when I read it. The othering and alienation born first of trauma, and decades later chronic pain (its own form of trauma), led me to be more vigilant. As a teenage girl, traumas led to biological and behavioral changes that shielded me from more violence. Not perceived threats, actual threats. It was a vigilance born of necessity. A vigilance that protected me and helped me to survive. My armor.

Let’s add a little more vigilance to the mix…

And then I became a firefighter, and my vigilance made me a damn good firefighter, too. That armor - being tough, a badass, a fighter, helped me make it in a male-dominated profession. As a firefighter, I was taught how to be even more vigilant, in more contexts. Always looking for and planning for problems, even when none are evident, because that's our job. I was already pretty damn good at looking for and planning for problems, even when none were evident. Like most women, it was a skill I’d honed over the years. I was vigilant as fuck. And a damn good firefighter.

It wasn’t just on calls that I needed to be vigilant, though. I was explicitly told by guys I worked with they didn’t believe women belonged in the fire service. I listened to sexist jokes and degrading comments about women, not standing up for them, for myself, because I wanted to be successful. I got along to get along. As one of 25ish female firefighters in a department of nearly 1000 firefighters, I did my best to be ‘one of the guys’,. I wanted to be accepted, respected, not realizing at the time that being ‘one of the guys’ was neither acceptance nor respect. I reinforced that armor I built as a kid, because it was evident that my armor was indeed necessary.

Vigilant af, indeed.

Of course it wasn’t all the guys, but it doesn’t have to be. If just one guy makes it clear you are less than, that you’re meant to be dominated or threatened or put in your place, you are on guard. And when those good guys don’t stand up for you, too often you stand alone.

So you got all that going on, and you do your job answering emergency calls for a living. An awesome job, I friggin loved it. I loved being a firefighter. I loved being a paramedic. I loved it, even though you see some shit on the job. Sometimes some really hard stuff, I won’t get into the details but any of you in emergency medicine know what I’m talking about. We see some stuff, and are not always taught how to deal with those cumulative traumas that are pile atop our own. And we are taught vigilance, yet never taught how NOT to be vigilant. At least not in my day.

Ok, so here we are now, in my early 30s, working a job I love, vigilant af out of personal and professional necessity, and then I get hurt. It’s no big deal at first. I work another 5+ months. But the pain doesn’t resolve like it should, so I’m thrust into the workers compensation system.

The trauma of work comp

If you’re not vigilant before going on work comp, you’ll become vigilant in a hurry. In work comp, they start from a place of denial and a belief you’re trying to game the system. So before you get care, you have to prove you’re not a liar and a cheat. You have to prove your worth, your decency, and also prove your pain, over and over and again. You have to fight for care, over and over and over again. This all while you’re least capable of fighting for yourself because you’re in so much damn pain and have a gazillion stresses (how are we going to pay our mortgage? When will I be able to go back to work? When will I be able to do the things that make me feel like me again? What does this mean for my future?) and have the least capacity.

I once went four months without any care at all, and no contact from anyone who cared, neither from work comp or from my fire department. I failed all the treatments that work comp approved and that I had to fight for. Fight for treatment, fail treatment, get punted to the next person with their promise of a fix and all the hope that comes with it, followed by another devastating failure, repeat the cycle, over and over, until told - after medications, physical therapy, injections, surgery, acupuncture, you name it - there is nothing more that can be done. You're on your own.

The ongoing trauma of care, and the abandonment we often experience when our pain doesn't fit into neat biomedical boxes, is legit. And when we don’t fit in those neat boxes, it’s not just healthcare that doesn’t handle it well. Our workplaces, families, friends, might not handle it well either. For all sorts of reasons. Socialization, ableism, capitalism, paternalism, fear, denial, sorrow, limited capacity to deal with their own shit, let alone our shit.

During those dark years of my pain, work comp was not looking out for me, despite being in charge of my health care. Nor was my department, despite my being a damn good employee who did everything asked of me. Hell, I was even accused of malingering by a Battalion Chief I used to work with. A guy I’d believed had accepted and respected me as a firefighter and friend and human. Ha! Was I wrong about that.

I was alienated even more, stigmatized further, thus making me ever more vigilant. Vigilance born of necessity, because we don't just think we aren't safe, we aren't safe. My health was on the line. My financial security was on the line. My future was on the line.

It was a lot.

There’s lots of ways vigilance becomes necessary

Of course this is just a glimpse into my experience, yet I’m sure plenty of people can find their own echoes here. We are alienated and othered and stigmatized for many reasons. The color of our skin, our ancestors, our religion, who we love and how we love, our disability, our birth place, our zip code, our bank account, our education, our weight, our gender. Experiencing ongoing pain that doesn’t make sense and doesn’t get better is itself traumatic, especially with all this other bullshit to deal with, especially in the US health system.

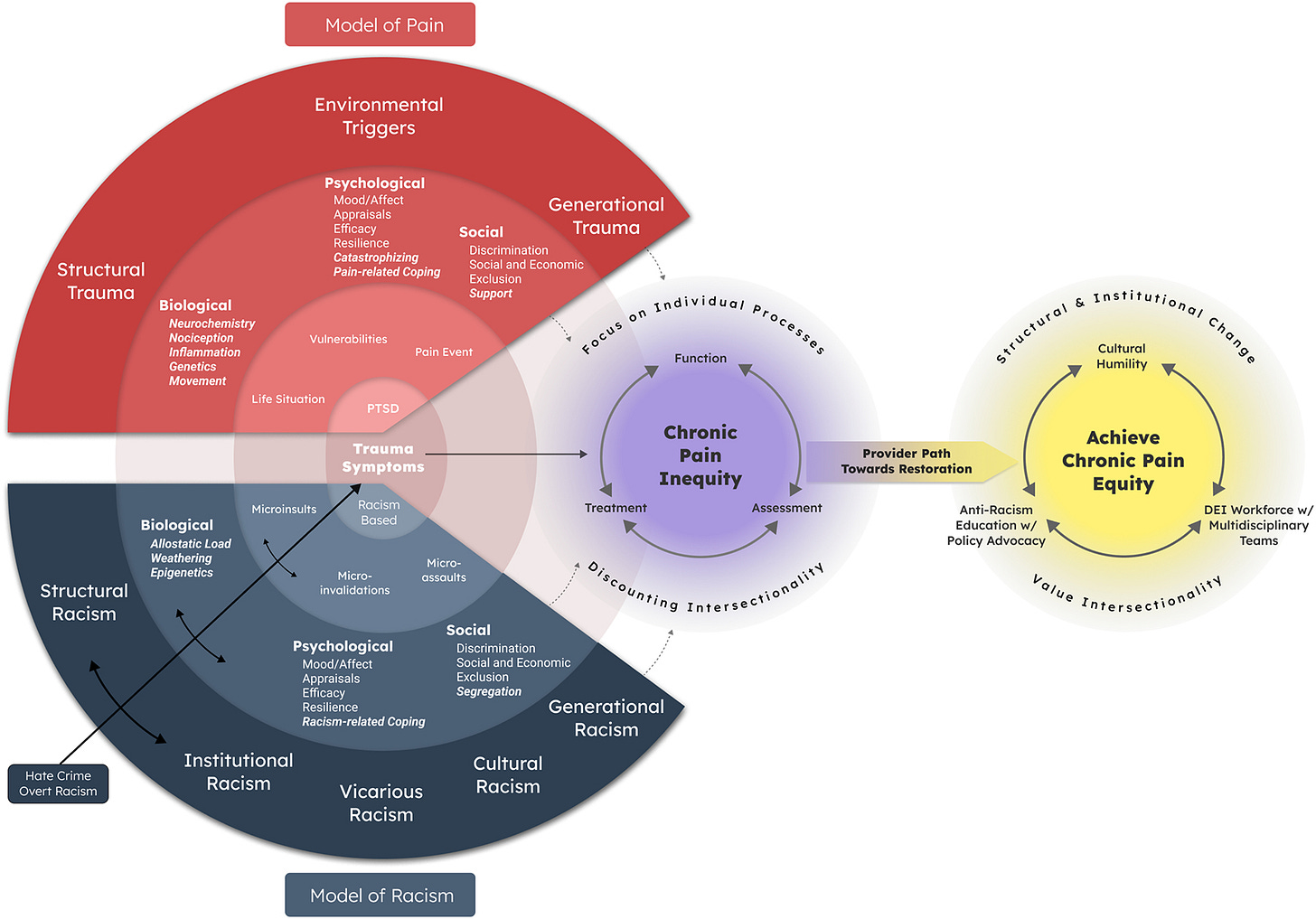

There are many ways we become vigilant that are not inherent to who we are but rather to how we are viewed and treated in society because of who we are or how we present. It’s that ACEs tree, and some things the tree is missing. To fill in some of those gaps, check out the amazing RESTORATIVE Model below by my friend Anna Hood and some other incredible folks, which visualizes how racism, trauma, and pain are related. Yet we keep focusing on fixing the individual, rather than on what is causing the trauma.

There’s a whole lot of us that are vigilant, for a whole lot of reasons. Maybe it isn’t our vigilance that is the problem, maybe it’s the things that require us to be vigilant that are the problem. As one of many examples, even if you’ve never been assaulted, you are affected by a culture that places the onus for not getting assaulted on the victim rather than the predator. Where we’re taught to modulate our behaviors, our language, our dress, our talk so as not to attract the wrong attention or invite violence or harrassment. And when we speak up against these things we’re called too emotional, weak, crazy, irrational, illogical, angry, hysterical, unfit, incapable, inferior.

This is still happening right now, not in some long ago history. And it’s about to get a whole lot worse for a whole lot of people in the US, which will have ripple effects throughout the world.

We are vigilant because WE HAVE TO BE. Against real threats, not just perceived. We catastrophize because we’ve had to plan for the worst, had to look for trouble where no trouble is evident, and hope for the best. And right now, after this election? Trouble is evident, not even hidden.

What am I getting at with all this?

I’m not writing all this to try and make clear links or explain things. I’m sharing because we so often try to make the complexity of humans - especially humans dealing with pain or trauma or health issues - so simple. And by doing so, we place the onus on the individual, without looking at all these other things that play a role (the social we so often miss in the biopsychosocial).

We’re pathologized for being human and adapting and surviving. We’re labeled catastrophizers or hypervigilant or our thoughts or behaviors are labeled maladaptive, harmful, dysfunctional, abnormal. More othering, more alienation, thus more vigilance. A vicious cycle too many of us get stuck in. But maybe being vigilant, planning for the worst, thinking a certain way or acting a certain way, has actually helped us survive in a world where we don’t critically interrogate how things like misogny, racism, homophobia, xenophobia, ableism - hate and discrimination of all kinds - affect our society, our policies, our health, our pain, our lives, our selves.

I know there’s also the stress of having to FIX ALL THAT. If I come into your clinic, your office, your program, how do you fix me, in light of all these things?

You don’t. You don’t have to. I don’t need to be fixed. You’re probably never going to know about the traumas I’ve experienced. Good news is, you don’t have to know the details to recognize we’re complex, messy humans who have been through, and are going through, some shit. To be kind and compassionate. To start from a place of love, not hate. To not judge or make assumptions. To see our strengths and hope and motivation because we’re STILL HERE, still seeking answers, still trying to find our path forward. To believe us. To trust us. To sit or walk alongside us as we figure this shit out together.

Your belief and trust enables us to set down the weight of not being believed, not being trusted. Your nonjudgement helps us get out from under the burdens of stigma and shame, discrimination and doubt. Without those burdens holding us down, maybe, just maybe, we can begin to rise up.

That goes a long way to fixing the bigger things that need fixing. The roots of these problems, the reasons why vigilance becomes necessary in the first place. Much more on that later.

For now, the LEAST we can do is make healthcare a place that minimizes threat, rather than ramps it up. A place that removes barriers, rather than erects them. A place that actually facilitates health and care, recovery and healing, sense-making and moving forward, peace and safety, bravery and compassion, connection and community, hope and love.

Wouldn’t that be something? Isn’t that something we all need?

Thanks for being here, folks. I’d love to hear what you think.

I’m shocked at the negative response to such a realistic post - it demonstrates that truth hurts. Your justified anger at your supposed “healthcare” providers and administrators resonates with me. I, too, have felt almost unbearable frustration that the force dominating and wrecking my comfortable life (pain) makes so little impression on the people in charge of our care just because they can’t measure it.

The truly big and important things/events/feelings in life rarely submit to measurement because they impact us on a deeper, invisible level, where they alter the course of our lives.

Just because they haven’t found a way to measure it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. It only means they can’t rely on numbers to tell them what to do (and these days “healthcare” is often run on irrelevant numeric standards, like MME). They have to rely on our self-reports, which are often strange enough to arouse their suspicion. Only the best, wisest, most experienced doctors learn to see the pained truth in our eyes as we tell of our suffering (which is not quite as optional as that saying about pain.)

May you find more compassionate and kind care as you wind your way through the cancer treatment industry.

Beautiful beautiful writing Jo! You've helped me see below the waterline of the iceberg that is vigilance which is so insightful, you're a wizard to be able to articulate things like you do. I love how you've managed to highlight some of the root causes of why vigilance has been needed for survival. Recognising your strengths and harnessing them towards your goals is such a valuable part of a better life. Stopping someone from being vigilant is a nonstarter (that many therapists still try) but helping them redirect the vigilance to more helpful behaviours is possible in an environment where people are believed, validated and compassionately supported as they are where they are.

I hope your breast cancer experience where what is happening isn't doubted and you have nothing to prove or anyone to convince has given you a taste of where ongoing pain care will be in the future, and you're part of that change in your bravery to speak up and get on those podiums.

Much love ❤️