Why does pain become chronic?

Out of many pains, and many surgeries, only one of my pains didn't go away

There’s lots of new subscribers here, so I just wanted to say hello before diving in to pains that become chronic, and pains that don’t. I’m sure many of you came here by means of other writers, and I hope you’ll stay. MyCuppaJo is a place to get curious about pain, health, and being human, from many different perspectives and ways of knowing - scientific, clinical, philosophical, lived and living experience, and art. There’s a good community of folks here, and I encourage everyone to engage in the comment section and have a good chat.

Now onto some pain things! While I took a step back from most of the projects I was working on when I was diagnosed with breast cancer last summer, I stuck with a few, including the National Institute’s of Health (NIH) strategic planning process for their HEAL initiative, where scientists seek solutions to the ongoing problem of pain.

As part of the strategic planning process, NIH held a number of workshops, including a Pain Research Priorities Workshop on Optimizing Interventions to Improve Pain Management, where I gave a brief presentation.

The idea of optimizing interventions is an interesting one. How are we defining optimal? Who are we optimizing pain management for? So much research is done in academic health institutions, is that the best way of finding solutions for most people living with pain? How involved are communities and people living with pain in the process? What can we learn from lived experiences of pain to ask better questions and develop better treatments?

My presentation was on my own pain experiences, of which I’ve had many. Yet only one of those pain experiences became chronic. Why? I hope research can answer that question, as I’m surely not alone in my experience.

I’ve edited the presentation a bit to make sense in this format, doing away with the thank yous and whatnot, and adding some context and a couple links, but below is pretty much what I said. You can also watch or listen here if you’d like. I start at about the 16 minute mark if it doesn’t automatically take you there (or watch the whole thing!).

Optimizing Interventions to Improve Pain Management: one story among millions of stories

I’m going to share some of my story of pain and treatment, just a glimpse into years, decades, of experiences, interactions, treatments, and reflections, and it is just that, one person’s story, amongst millions of stories of pain and perseverance.

I became a firefighter in my 20s. In the images below you see me on my first structure fire, my first big wildland fire, and leading a bunch of teenage fire explorers into a refinery fire training drill.

I LOVED my job, and if you’d asked me to describe myself, I would have answered, I’m a firefighter, and to me that encapsulated all that I was. I was also a paramedic, and a peer fitness trainer - to totally brag, I was jacked - leading morning physical training for our fire academy recruits and designing and delivering workout programs for our firefighters and civilian staff.

Then, one day, I stepped off the fire engine as I had thousands of times before, but this time I missed the step and felt a twinge in my hip. just a twinge, no big deal, I still worked as firefighter/medic for another 5 months. But that missed step, that twinge, set me on a path of ongoing worsening pain that did not respond to treatment, did not get better like it should have, and turned my life, my world, my self, upside down. That very specific pain in my hip, in the words of Drew Leder, diffused like a malignant mist throughout my experienced world.

The world as a whole could feel vaguely menacing; or drained of all color and warmth; or something muffled and far away, as if one dwells on an isolated island. In such ways, the pain of a small and particular thing—my ankle pain, another’s kidney stone, or aching tooth—can totalize itself. The specific pain diffuses like a malignant mist throughout the experienced world.

~Drew Leder, The Experiential Paradoxes of Pain

That missed step, that specific pain, that malignant mist, led to the darkest years of my life. Years I was still working, in a civilian position, although I don’t remember much, everything is obscured by that malignant mist. But I do remember this. Going to yet another physical therapy appointment, in yet another clinic, and standing at the counter filled out endless forms yet again, when the receptionist looked into the treatment area and told the physical therapist that her 2 o’clock hip was there.

This image, created by my friend Soula Mantalvanos, reflects how I was seen over those dark years. It’s even more apt, because for part of that time, my leg did not feel like my own. Of course I knew it was mine, but it didn’t feel like mine. I’m grateful to Oliver Sacks for writing A Leg to Stand On or else I would have felt alone and crazy in that experience.

During those dark years I saw countless doctors and health professionals, underwent a lot of treatments and therapies (everything starred was outside the health system, paid for out of pocket out of desperation to just get better). Everyone had a different diagnosis and plan to fix me, all of which I had the highest hopes for, all of which crashed into despair when yet another thing didn’t work it was a confusing time, too, as many of the diagnoses and proposed treatments were contradictory, both within and across professions, until I reached the point that I was told there is no more that can be done and I was left to figure things out on my own.

Before chronic pain, I had many pains (and a few surgeries…)

Now, usually when I tell my pain story that’s where I end, then I talk about what I did and how I got better - not pain free, but better - and what went wrong and potential solutions, but today I want to talk about what came before this chronic hip pain, too.

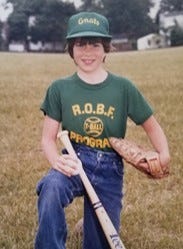

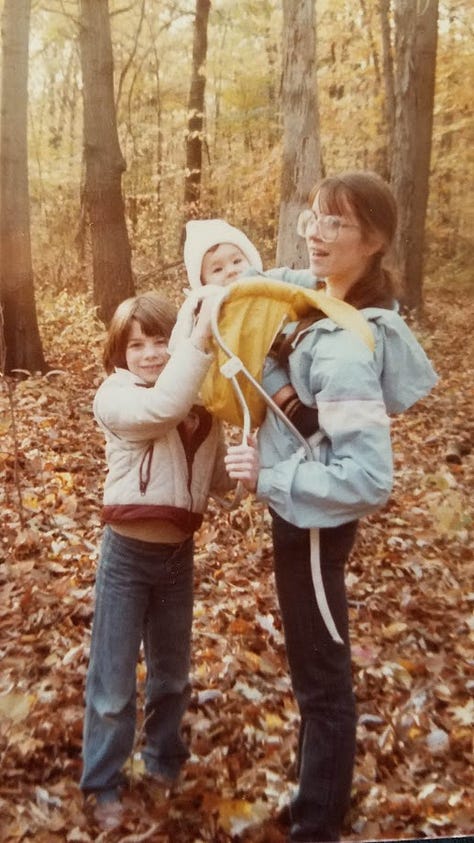

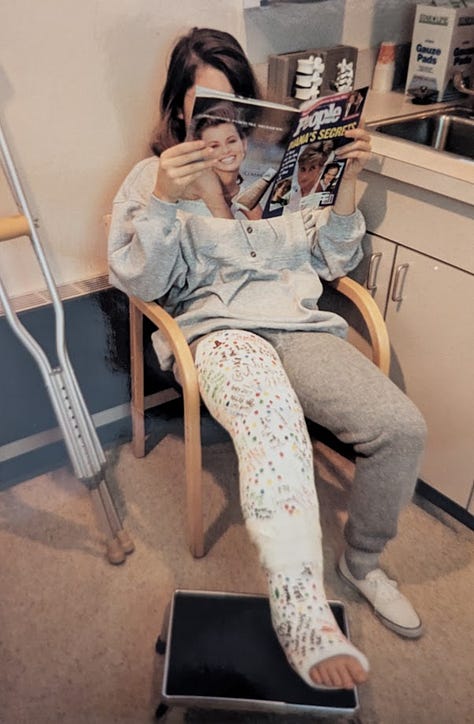

I grew up in a blue collar family in metro Detroit, born to teenage parents (the middle picture is my mom, me at 7, and my brother). I was an athlete from the time I could walk, don’t let the jeans fool you (that’s me T-Ball. We were the gnats. Who wants to be a gnat? Everyone called me Joey then, I was a total tomboy), until I was hit by a car - driven by a senior - my junior year of high school the night before Powder Puff. (If you didn’t have Powder Puff, it was senior girls vs junior girls in flag football.)

I long thought the thing that set apart my hip injury was the threats to my identity, no longer being an athlete, not being a firefighter Until I pulled out this old news clipping last week, which outlines my injury and comeback. I’m quoted about how I couldn’t fit in my friends cars, couldn’t do anything, was depressed. That I had been a basketball player, volleyball player, softball pitcher. That I’d lost my identity.

Yet back then, as soon as my cast was off, I was back to playing sports. No ongoing pain issues, ever. I’ve also had 4 broken noses for which I had to have two reconstructive surgeries – from 2 softballs, an elbow in basketball, and an unfortunate dancing incident, and I’ve also had my wisdom teeth pulled. so that’s 4 surgeries under anesthesia and no pain problems. I mean, I once played an entire softball game with a broken nose, that Detroit vs everybody, blue collar upbringing in action.

After chronic pain, I’ve had many pains (and a few more surgeries…)

But what about AFTER my chronic hip pain? In previous presentations I’ve talked about going back to grad school in human movement to better understand my pain and what I could do about it (not a viable nor desirable nor affordable treatment path), being an adaptive snowboard coach for athletes with disabilities and having to unlearn much of what I learned in grad school, and how I try to make sense of things through writing.

I’ve talked about my advocacy work to integrate lived experience into the work of pain and the research partnerships I’m a part of, my patient and public partnerships editorial role at JOSPT, and cool initiatives I’ve been involved in like ENTRUST-PE and PXP, but I've never talked about my other pain issues.

Yet, years after my hip pain, I had severe pelvic pain. It turned out to be fibroids, the largest bigger than a grapefruit and sitting on my bladder. I had a hysterectomy, and yet again no pain problems. In fact, I felt fantastic immediately after I woke up from surgery. Better than I had in years while I was still in the hospital, and it was an outpatient surgery. I felt so good I had a giant spaghetti and meatball dinner that night (after which I did not feel so good cuz anesthesia).

And, just this year, I was diagnosed with breast cancer, which came with yet another surgery, again with no ongoing pain problems. Actually two surgeries, just three months apart, and no issues with pain for either, even with just alternating Tylenol and ibuprofen as my only pain relief in the early days after both.

I was the same person for all these surgeries, not to mention countless other sprains, strains, muscle tears, illnesses, and traumas. The same hypervigilant catastrophizer. Yet pain ONLY became chronic for my hip, not for anything before or since.

There’s a bit of a caveat there, as I’d actually had pelvic pain since I was 13, but it was never called chronic pain, and I never had a diagnosis other than ‘it sucks to be a girl’ until they could SEE a grapefruit where it shouldn’t be.

Fun fact, post-pathology after my hysterectomy I was also diagnosed with adenomyosis. Which I’d probably had for years, I’d certainly had symptoms for years, but I thought that having all that pain and heavy bleeding every month was just normal. So I just put on my big girl pants (and period panties) and dealt with it. For more than three decades.

(For more, check out “Just” a painful period: A philosophical perspective review of the dismissal of menstrual pain by Jada Wiggleton-Little)

So it wasn’t duration of pain prior to surgery that led to my hip pain becoming chronic, either. And we’ve already seen it wasn’t an identity crisis or my life and self being upended. Though that surely didn’t help, it was not a cause. Been there, done that. It wasn’t a weak constitution.

With my breast cancer experience, while my care team has been wonderful, there are other challenges, the biggest of which is not having ANY oncology services in my county, none, so I have to travel a minimum of 3 hours round trip to every appointment, or, as is the case currently, get a hotel for daily radiation - I'm speaking from the hotel now, so it’s a bit disruptive and I’m incredibly privileged that I CAN stay in a hotel for treatment (thankfully it was paid for by the hospital’s philanthropic foundation because we don’t have radiation services in our county or neighboring counties).

Also, until I met my out-of-pocket maximum - which was a lot - the first person I saw for all the appointments I traveled so far for was the person who wanted me to pay for services up front, before I was even seen by a health professional. That’s stressful, you know? It sets a tone that YOU don’t matter, your ability to pay does.

So what was it that led that one particular pain to become chronic?

As we can see here, as we all know, the health system has its own threats, challenges, stresses and barriers, so what was it about my hip experience that made it chronic? I was the same person for all these injuries, all these conditions, all these surgeries, yet pain only became chronic for my hip. I was the same hypervigilant catastrophizer, with the same trauma history, the same life experiences, yet only one pain of many pains didn’t go away.

Was it being in work comp that was so different? Was it having pain that didn’t fit neatly into a biomedical box that was so different? Was it stigma? (For more on stigma and the harms of needing objective proof of pain, check out this chapter by Daniel Goldberg on Pain, Stigma, & Neuroimaging: History, Ethics & Policy).

Was it distrust of patients with pains that aren’t readily explained, or readily fixed? Is it because pain is invisible and not believed in the same way a fractured leg or broken nose is believed? Or a cancer diagnosis is believed? Is it because certain folks among us (women, Black folks, Indigenous peoples, immigrants, poor folks, LBGTQIA+ folks…the list is long) aren’t believed like others among us are believed? IS it all of these intersecting and overlapping things?

I don’t know, I’d love to know what it was, I hope research can figure it out one day!

So why am I telling you all this?

Because I think living pain and pain treatment is an important way of knowing pain that can help us as we think about what optimal pain care can look like, and what research needs to be done to get there. This is my story alone, yet I am not alone in many of my experiences, sometimes we find the universal in the specific.

Many people have had injuries and illnesses and surgeries without pain problems, then suddenly have a pain that becomes chronic. Many people are in adversarial or confusing or stressful work comp or health insurance situations. Many people face barriers to care, such as finances, access, acceptability, transportation, travel, needing time off work, family responsibilities, bias, discrimination, disbelief, and stigma - atop all their other expenses, time commitments, responsibilities, and struggles.

Because optimizing pain management for folks can mean a lot of different things, look like a lot of different things., There is no one-size fits all approach to pain, even for the same individual across time, as my story shows. The only way we can improve pain management is through learning from, with, and alongside a diverse group of people living with the conditions or symptoms we are trying to treat or prevent. This is already baked into the NIH HEAL initiative, and these partnerships between communities, people with lived experience, and scientists are vital to the success of whatever research priorities are set.

There are many ways of knowing

For me this means meaningfully integrating the knowledge and insights of people with lived and living experience or pain, across the lifespan, throughout the entirety of research process – from setting priorities as NIH is currently doing, to study design and data collection, analysis and interpretation, to dissemination and implementation in the real world, from urban centers to rural areas and everywhere in between. To be successful, we have to prioritize building trusting relationships and facilitating collaborative partnerships between researchers and communities, between people with scientific knowledge and expertise in pain and people with lived knowledge and expertise in pain.

By bringing scientific knowledge together with the knowledge gained from lived experience, better research questions may be asked, even at a molecular or mechanistic level, and more innovative and transformative treatments may be discovered.

Blair Smith & Joletta Belton, Patient engagement in pain research: no gain without the people in pain

The best science is driven by curiosity. We do not know all there is to know about pain, and our current theories of pain will evolve, and some will be proven wrong altogether. We (at least most of us, most of the time) no longer believe pain is punishment for our sins, or that pain is housed in the pineal gland ala Descartes, or that we just need to adjust one of our four humors for better health. It is hubris to think that science, or clinical training based upon health research, are the only ways to know pain. We need the knowledge and wisdom gained from diverse lived and living experiences, lived ways of knowing, to drive better questions and collaboratively design better solutions.

Why did that one pain, of all my pains, become chronic? It’s a good question for science, but I don’t know if we’re asking the right questions to get us closer to the truth. It’s a good question for all of you, too! If your’e so inclined, share your thoughts in the comments.

Thank you for your blog, Joletta. I found you googling, and your story is so similar to mine: On a climbing session I moved weird and got a minor hip injury, that didn't respond to physiotherapy and developed into chronic pain. The scans show really minor scarring that isn't in sync with the pain.

My journey is different in that I came across modern pain science really early on. The knowledge unfortunately didn't cause a breakthrough in my pain experience the way it did for you and for many other people. Maybe the timing was wrong? (But I'm prone to overthinking, and focussing on getting everything right in order to get out of this maze often isn't helpful.)

Why did this get chronic? I've had my share of injuries, and they all cleared up eventually. Was it because I felt socially isolated and distressed when I couldn't do any of my favourite sports? Because I googled my injury too much? Did too much psysiotherapy? Too little? Does it even matter, since I can't go back and change anything?

But I'm moving. I'm on the climbing wall again, I bike, I can walk up to an hour without flaring up too much. I tell myself there's nothing wrong with my body, and that my alarm system is just overprotective.

Your journey out of the fog of pain and back into life is a source of hope for me!

Thank you for this kind and generous share. The ability to get curious and explore different options for care is crucial, I think. As a physical therapist, it is vital for me to listen and see the whole person. You are not just your hip, but I can’t tell how embarrassed I am to admit that I have lost sight of the human in front of me and seen only their hip far more times than I care to recount. This is a gentle reminder for me to listen, collaborate and use my skills for good.