You want me to accept what? Navigating acceptance and chronic pain

Revisiting the concept of acceptance with the help of an award-winning poster by Cass Macgregor and her team

Imagine you’re just cruisin’ along in your life and all is groovy then, suddenly, unexpectedly, it is completely, utterly upended. You’re forced to leave your career that had defined you. You lose your circle of friends because you can’t do the things you used to do anymore. In losing your job, your financial security, your day-to-day activities that brought you purpose and joy, you also lose yourself. Every day is a struggle.

Could you accept that? How long would it take? What would it take?

Acceptance is often recommended as helpful for people struggling with chronic pain. From my own experience, that can be true. But what do we even mean when we say ‘acceptance’? What exactly are we accepting?

After all, some things are unacceptable when it comes to living with pain and seeking care. There are biases, discrimination, racism, sexism, homophobia and all sorts of other isms and phobias that not only contribute to people’s experiences of pain, but also to their experiences seeking care and receiving treatment (or not receiving treatment at all).

Too many people with ongoing pain are doubted, disbelieved, dismissed. There is massive stigma associated with chronic pain1, which can be compounded by other stigmas related to sex, gender, weight, education, income, employment, housing, substance use, disability, mental health diagnoses, and so on.

It’s really hard to accept things when you’re not believed. When you have to constantly prove your pain (thus having to prove your worth and value as a human being). It’s really hard to accept not knowing what’s going on, not having a clear diagnosis or explanation for your pain that makes sense to you. It’s really hard to lose so much because of the pain. To lose yourself because of pain.

How does one accept all that?

These things are unacceptable to me because it doesn’t have to be this way. These are things that can change, that need to change. (This is why I became an accidental advocate - wanting to change the unacceptable!)

I won’t accept sexism, racism, discrimination, stigma, or gaslighting when it comes to pain care.

I won’t accept a worker’s compensation system that is so difficult to navigate and so damn adversarial, out to prove we’re gaming the system instead of providing adequate care. (This not only sucks for people being treated - or not - in the system, but also for the health care professionals trying to treat them).

I won’t accept people with pain being doubted, disbelieved, dismissed. I feel this one in my bones. During the worst of my pain and uncertainty I was accused of malingering by someone I had trusted and respected at my old fire department. It was a devastating, demoralizing blow. Still is.

I won’t accept the many bogus explanations people are given for their pain. I was told some pretty wacky stuff, like my spine was twisted on its axis, or that my broken tib/fib nearly twenty years before was the current cause of my hip pain. Nor will I accept all the broken promises that fixing X (anatomy, posture, biomechanics, movement patterns, etc) would fix my pain. (Most of these explanations and ‘fixes’ were not based on evidence and current research.)

We need to do better. We can do better.

Yet I can accept where I am. I can accept the reality that some of things happened - even if those things were unacceptable. I can accept the good and the bad that led me to where I was during the worst years of my pain, that led to where I am now, while also not accepting that these things still happen to millions of people.

So what I’m saying, I guess, is that acceptance of chronic pain is no simple or easy task, down to what it is that we’re even supposed to accept. Even as I write the words above, so so many years later, I still feel anger and frustration - I clearly still need to work on this acceptance thing ;). Yet with myself, with my present moment, I also feel at peace. It’s a tension that’s hard to explain.

How do you capture all that in any sort of definition or description of acceptance?

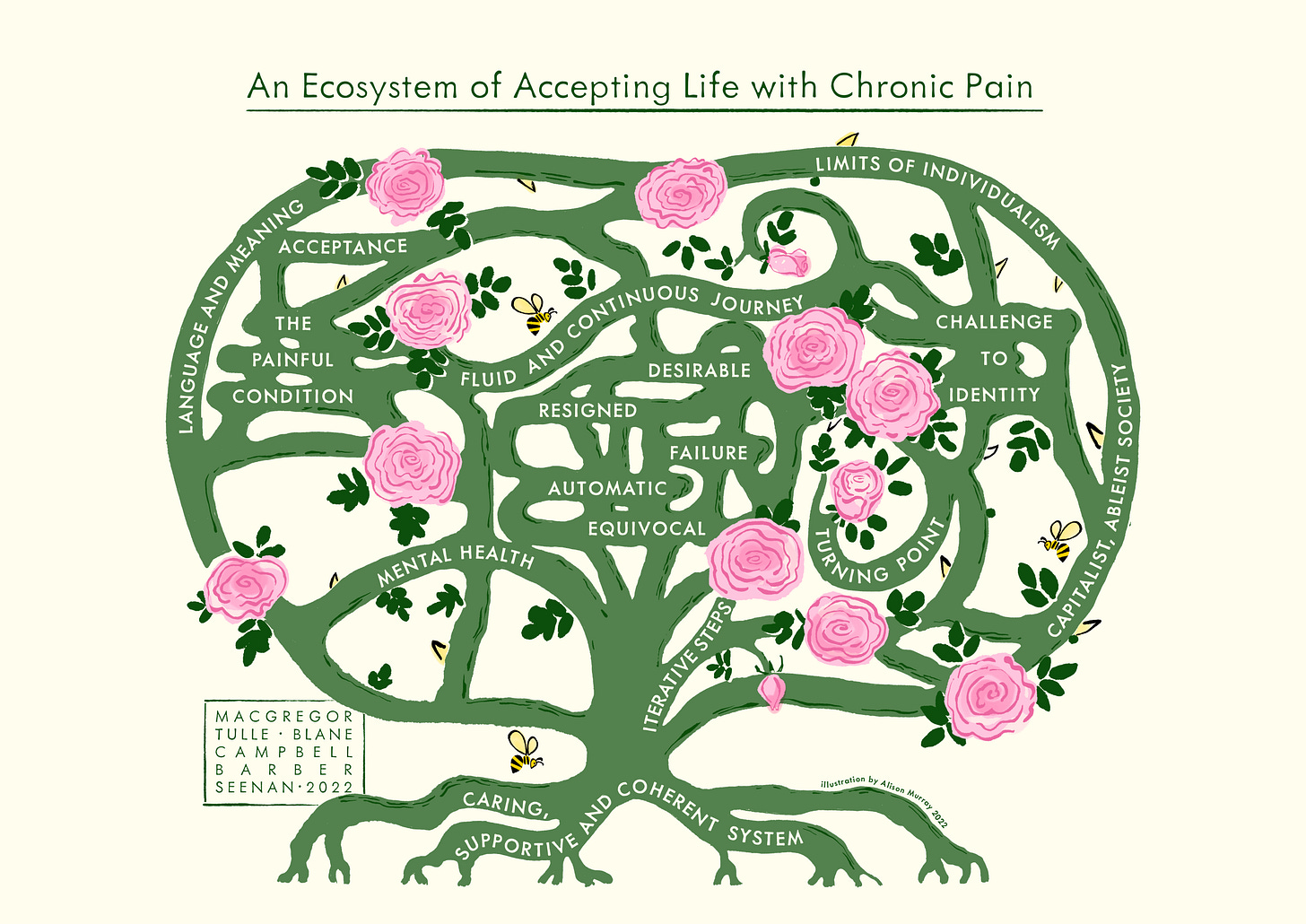

This is why I LOVE Cass MacGregor’s PhD work on acceptance. Cass and her team (Emmanuelle Tulle, David Blane, Claire Campbell, Ruth Barber and Chris Seenan) recently published an award-winning poster ‘An Ecosystem of Accepting Life With Chronic Pain: A Meta-Ethnography’. The poster is brilliant in summarizing their framing of such a wrought concept such as acceptance. The imagery is incredible. This poster captures what I’m trying to say much better than I ever could!

There are flowers and thorns, beauty and pain, all at the same time, fluid and interconnected and complex and ever-changing. Including how the very meaning of acceptance is so hard to put into words, how difficult (impossible?) it is to agree on a singular meaning. Not just between different individuals, but also within ourselves. Meanings change over time. Our relationship to acceptance, and to pain, changes over time.

I don’t know if we can ever achieve ‘acceptance’. Probably in anything, and maybe especially acceptance of chronic pain. It’s too fluctuating, too nebulous, too multi-faceted. Acceptance is something we may fall in and out of over time, and that’s okay.

One of the biggest challenges may well be the limits of individualism (in Western biomedicine in particular) that Cass and her team explain so succinctly in the poster. This individualistic focus is not just problematic when it comes to acceptance, but also to pain, health, treatment, recovery, success, and failure.

When we focus solely on the individual there is room for so much judgement, so much stigma2, and can lead to us being blamed for our pain, especially when there is no readily identifiable underlying cause - a lesion or clear pathology that can be visualized and ‘made real’ (scare quotes are because that’s bullshit! All pain is real, even when you can’t see it on a scan or some test) - that can explain it3.

This blame isn’t always explicit. In my experience, it’s often not. But it’s there. And we know we’re being blamed. Especially if we don’t get better like we should have, when we fail all the treatments (in the vernacular of health care, the treatments never fail us). This focus on the individual - on me, on you - as the cause of all our our problems and the sole force of our recovery ignores the inequitable systems, structures, processes, policies, beliefs, and attitudes that affect our health, our pain, our ability to recover or heal or live well.

Is that acceptable?

Can you accept my pain?

It’s also one thing for me to accept my pain, to accept how much pain upended my life and self, to accept any limitations I have because of that pain. It’s a whole other thing for others to accept it. For society to accept it. For employers, co-workers, partners, family members, friends, strangers at the grocery store to accept it.

If any of them cannot accept me with my pain - or you with your pain - where are we left? Should we just accept that too? Where does the acceptance end? Where does it begin? What are the parameters of what we must accept?

And yet…even with all of this, somehow acceptance has been helpful for me and for others.

I eventually came to understand that acceptance wasn’t giving in to pain or giving up on myself. Acceptance wasn’t accepting the unacceptable, either. Rather, it was just accepting my current reality and no longer fighting a past I could not change. It was accepting my current self (who I kinda like, most of the time).

Acceptance is not resigning myself to shittiness, either. Accepting that certain things happened is not the same as accepting what happened. I can accept the reality of those dark years of ongoing, unexplained, worsening pain and all that came with it, and also fight like hell to change the future.

How do we change the future?

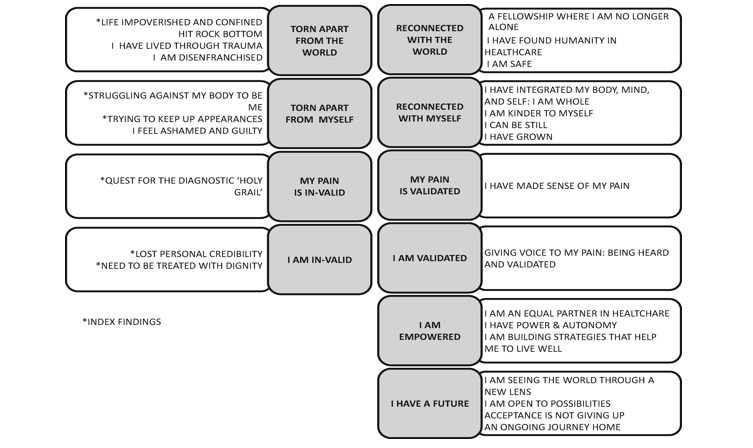

It is telling that in another recent meta-ethnography led by Fran Toye (which I was fortunate to be a part of) that acceptance is one of the last concepts in the model of ‘a healing journey with chronic pain’. So much comes before it, so much that aligns with the poster by Cass and her team.

There’s a lot of shit people with chronic pain have to go through. Our own shit, surely, but also shit imposed upon us by the ableist, individualistic systems and societies within which we live and seek care.

With pain, especially ongoing pain, we can become disconnected from the world, which often sets us apart and isolates us when we do not conform to ‘the norm’. We are often dismissed or doubted, which contributes to shame, guilt, feeling unworthy. We search endlessly for explanations, not just for our pain, but for ourselves with pain. We become disconnected from ourselves. We lose our identities, our social roles, our sense of who we are and who can become.

It’s hard to accept all that. It’s no wonder we often don’t. At least not until a bunch of other things fall into place. This is where we can make a big difference.

To even begin to accept chronic pain - if that is something we desire to do - we need explanations that make sense to us. We need to be treated with dignity and respect. We need to be supported and validated, cared for and cared about within compassionate, equitable, and ethical systems. Systems that are not just compassionate and equitable and ethical toward us as people seeking care, but also toward those of us who provide that care.

We are all humans, after all, and this chronic pain stuff ain’t easy! What if we used meta-ethnographies such as these to point the direction toward a new and better future of pain care? Could they serve as jumping off points for people with pain, researchers, clinicians, policy-makers, and community leaders to come together to craft more equitable, ethical, and compassionate ways forward?

…there are many truths and there are many ways of knowing. Each discovery contributes to our knowledge, and each way of knowing deepens our understanding and adds another dimension to our view of the world.

Ann Hartman, Many Ways of Knowing, 1990

One final note, related to the quote above. These meta-ethnographies led by Cass and Fran don’t just explore the lived experiences of people with pain, they explore these experiences with people living with pain. Both research teams included people who have lived what is being studied. That is invaluable.

It only makes sense, doesn’t it? Yet it’s not done enough.

When it comes to questions to ask about pain, to developing concepts that define or explain or explore pain, or to collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data about pain or painful experiences, people with pain ought to be involved.

We cannot understand pain - which is not some abstract concept to those living with it - or what can be done about it through science alone. We need the expertise, stories, insights, and perspectives of people living with pain - at all of the intersections of their experiences in the world - to even begin to understand the breadth and depth of the experience of pain and all that comes with it and all that can be done about it.

And we cannot provide ethical and effective pain care if we solely focus on the individual without also changing the systems, structures, and policies that have such a huge impact on our health and our ability to heal and recover and thrive.

We have to acknowledge and address all the isms and phobias. Working with people with pain who face these isms and phobias to uncover the issues and find acceptable ways forward is crucial.

We are all a part of these systems. We can be a part of changing them.

Together, we can we begin to change what is unacceptable. And we must.

Thanks for being here folks! As always, I’m curious your thoughts on all of this. Could you accept chronic pain? Have you already? What would/did it take? What about all these other issues surrounding the concepts of pain and acceptance that are included in these two meta-ethnographies? Do we have to accept those things, too? Does healthcare/medicine have a place in changing these things I’ve deemed unacceptable? What would it take?

Footnotes:

Here is a great overview from BMJ, beginning with the article Pain, objectivity and history: understanding pain stigma and a follow-up interview with Daniel Goldberg (the author of the first article) on Shame, Stigma and Medicine. There are more articles on stigma below. We need to address stigma, or else it’s going to be pretty damn hard to improve the lives of people with pain.

Here are a few more articles on stigma. Daniel Goldberg has been hugely influential on my thinking and his work in stigma and chronic pain is a great place to start when trying to truly understand the history of stigma and how that influences thoughts, biases, and attitudes in medicine (and society) today, particularly in the context of pain.

A great overview in The Atlantic: The Long History of Discrimination in Pain Medicine.

In STAT: Pain doesn’t stigmatize people. We do that to each other

In The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics (not open access, hit me up if you want a copy): On Stigma and Health

Also from Daniel Goldberg, in Developments in Neuroethics and Bioethics (also not open access, hit me up if you want it): Pain, Stigma, & Neuroimaging: History, Ethics & Policy

Awesome read Jo. I have shared it to our support group FB page and I hope that many will read it. It took me right back to those early days when acceptance was so difficult to come by in the light of "difficult" language from some HCPs. Fortunately, I had 2 HCPs who supported me, saved me from others 😀 and generally made my life liveable until I found my way again - with acceptance and a lot of help from others. Thank you so much!

Amazing that you’ve picked this up, Joletta. Does Cass know that you’ve written this? She’s doing great work